Forensic Analysis using QAUDJRN - Part 1 -

CL Command Usage

By Dan Riehl

In the first article of this series dealing with forensic analysis using the QAUDJRN journal, the focus is on the forensic analysis of CL command usage. I show you how to audit and report on every CL command run by a particular user and also how to audit and report on every use of a particular CL command of interest. As examples, I examine how to audit and report on every CL command run by QSECOFR, and I show how to audit and report on every usage of the Change User Profile (CHGUSRPRF) CL command.

What Is Auditing?

When I discuss the topic of auditing, I'm referring to the IBM i auditing capability in which certain predefined activities or events cause an audit log record to be written as a formatted journal entry to the system's audit journal QAUDJRN. Auditing using QAUDJRN isn't automatically configured, so when you first start your system, you must configure the IBM i QAUDJRN auditing to meet your specific auditing requirements as defined by the system administrator, the security officer, the security policy, and your IT auditors.

Once you've configured your auditing environment, regular reporting of the QAUDJRN activities and events should be instituted to ensure adherence to policy. When audit journal entries are written to QAUDJRN, you have the sound basis needed to accurately analyze and report on current and historical events.

Even assuming a regular QAUDJRN reporting regimen, there will be occasions when you need to go back and dig out past events. These past events may have negatively affected your system, or you may want simply to check on who did what, when. For example, you may want to determine who changed Fred's user profile to assign him *ALLOBJ and *SECADM special authority. When did it occur, and how was it accomplished?

In cases like this, you can use forensic evaluation methods to extract the relevant audit entries from QAUDJRN to determine the culprit. In recent cases, I have been asked to use the QAUDJRN forensic reporting methods to solve some interesting mysteries, such as:

- A particular user profile keeps becoming disabled. Why?

- An RPG program ran correctly on Saturday but ended abnormally on Sunday. Did someone change the program between Saturday and Sunday?

- Who changed the System Value QCRTAUT from *ALL to *CHANGE, and when did the change occur?

- How did a new file end up in a library with incorrect private authorities, when the library's CRTAUT was specified correctly?

- Who has used the UPDDTA(DFU) command, and what files were they viewing and potentially editing?

- What CL commands were run from the command line by all *ALLOBJ users?

- Who has run compiler commands (e.g., CRTRPGPGM, CRTBNDRPG, CRTCLPGM, etc.) to create new programs on the production system?

All these mysteries were successfully solved by using the forensic analysis of the QAUDJRN journal. It is important to note that I was able to analyze the audit entries because the customers were auditing the particular events that comprised these incidents. For example, if the auditing setup did not include the QAUDLVL system value inclusion of *SECURITY, I wouldn't have been able to discover who changed the system value QCRTAUT. Changes to system values are audited only when QAUDLVL contains the value *SECURITY or the sub-value *SECCFG>.

Is Your System Ready to Start Command Auditing?

If you're unsure about the auditing settings on your IBM i, you can use the Display Security Auditing Values (DSPSECAUD) command. Run the command to discover the current auditing settings on your system. If you see from the DSPSECAUD display that the journal QAUDJRN doesn't exist, you need to configure the system to start auditing. The easiest way to configure auditing is to use the Change Security Auditing Values (CHGSECAUD) command.

To audit command usage on the i, you must configure the QAUDCTL system value to allow auditing. In the case of auditing command usage, the system value QAUDCTL should be set to include the value *OBJAUD. However, in a standard auditing environment, you typically set the QAUDCTL system value to include the three values *AUDLVL, *OBJAUD, and *NOQTEMP.

Once command auditing is started, each audited command is logged into the QAUDJRN journal with a journal entry type of CD. Each CD journal entry identifies a command execution event.

(For more information about journal entry types, see Reference for QAUDJRN Entry Types).

Start Auditing for Every CL Command run by QSECOFR

Once you have your auditing configuration set up with QAUDJRN, you can begin customizing the audit environment with your specific requirements. To begin auditing CL command usage by a particular user, you use the Change User Audit (CHGUSRAUD) command. In the following example, we specify that we want to audit all CL commands run by the user QSECOFR:

CHGUSRAUD USRPRF(QSECOFR) AUDLVL(*CMD)

Start Auditing Every Use of the CHGUSRPRF Command

When we want to audit the usage of a particular CL command, we use the Change Object Auditing (CHGOBJAUD) command. Here's the command we would use to start auditing every usage of the command CHGUSRPRF:

CHGOBJAUD OBJ(QSYS/CHGUSRPRF) OBJTYPE(*CMD) OBJAUD(*ALL)

QAUDJRN Reporting Tools—Buy or Build?

Now that you're auditing the activities and events of interest, it's time to extract the data from the QAUDJRN journal receivers into useable information.

At the last COMMON Conference, I noticed that there were no less than five IBM i software vendors selling tools to extract and format the data from QAUDJRN. In the case of buy versus build on audit reporting software, it's usually an easy choice, as in the case of any utility type software. If you have a technical IBM i staff capable of putting together a robust QAUDJRN reporting system and maintaining it from release to release, and they have little else to do, building your own software may be the ticket. On the other hand, most commercial QAUDJRN reporting software is robust and supported, and like most IBM i utility-type software, it can be rather inexpensive (i.e., under $7,000 for a medium-sized system).

One of the most important questions to answer when considering buy versus build is, "Do I get all the reports I need, in a format I can use?" Some commercial tools provide reporting only to report spooled files, whereas others allow output to Microsoft Excel, IBM i *OUTFILES, PDF documents, and so on. Some tools provide a nice MS/Windows based interface, while others are green-screen text-based only. If your IT auditors are going to be users of the reporting tools or consumers of your reports, your solution needs to be able to generate output to Excel.

Building Your Own

Even if you decide to buy instead of build, your reporting tool will at times fall short, and you'll need to roll-your-own report for a specific instance. The IBM i operating system provides some nice tools to extract the data from the QAUDJRN journal receivers. Once the data is extracted using one of these tools, you need to determine what reporting tools you want to use. The reporting tools aren't part of the base operating system, and tools such as IBM Query for iSeries and IBM DB2 Web Query for i are an additional charge. But if you already have these query tools installed, like most shops do, there is no added software cost to building your own QAUDJRN reporting system.

Extracting the Data from QAUDJRN

The IBM i provides a few CL commands that you can use to extract the data from QAUDJRN. The main CL commands are Display Journal (DSPJRN) and Copy Audit Journal Entries (CPYAUDJRNE).

Note: The Display Audit Journal Entries (DSPAUDJRNE) command is no longer being updated by IBM and should be used only for the most basic extractions (e.g., AF entries). DSPAUDJRNE has in effect been replaced by CPYAUDJRNE in IBM i V5R4.

Using DSPJRN Versus CPYAUDJRNE to Extract QAUDJRN Data

To extract QAUDJRN data, the CPYAUDJRNE command is the easiest to use. However, the DSPJRN command can be favorable over CPYAUDJRNE because DSPJRN provides many more selection criteria options. For example, if you want to extract entries generated by a specific job, a specific program or a specific User, DSPJRN provides for that selection. DSPJRN also provides for several different *OUTFILE formats, again providing more flexible extraction options.

Recently, I wanted to extract and report on all "i>Object Opened for Change Access" made through the ODBC server job named QZDASOINIT. Using the DSPJRN command to extract the entry types of ZC (Object Opened for Change Access) made that an easy task because I could specify the job name as part of the extraction selection criteria, as shown here.

DSPJRN JRN(QAUDJRN)

JRNCDE(T) ENTTYP(ZC) JOB(QZDASONINT) USRPRF(*ALL)

OUTPUT(*OUTFILE)

OUTFILFMT(*TYPE5) OUTFILE(MYAUDIT/CD_ENTRIES)

But the CPYAUDJRNE command has definite positives going for it. The command uses a customized output file format specific to the journal entry type being extracted. In our subject case of CL command execution, the output file format used is the same as the IBM supplied file QASYCDJ5, which breaks out many important fields that DSPJRN usually doesn't. CPYAUDJRNE also lets you select entries based upon the user that generated the entry, but it doesn't allow for selection by the program or job, as DSPJRN does. Shown here is an example of using CPYAUDJRNE to extract CL command execution events by all users for a 24-hour period.

CPYAUDJRNE ENTTYP(CD) OUTFILE(MYAUDIT/CMDS)

USRPRF(*ALL)

JRNRCV(*CURCHAIN)

FROMTIME('12/07/2011' '04:00:00')

TOTIME('12/08/2011' '04:00:00')

In my trials of using DSPJRN versus using CPYAUDJRNE, I find that I like to use a hybrid technique that provides the best filtering capability for the extraction. That decision is really based upon the selection criteria and output formats available for each command.

Extraction Examples

If the DSPJRN command is used, there are a few output options that determine the length of the journal entry's Entry Specific Data (ESD). The ESD contains critical information that must be included in the extracted data. However, if you specify the incorrect parameters for the DSPJRN command, as shown here, this critical ESD can be truncated to only 100 bytes(JOESD).

DSPJRN JRN(QAUDJRN) RCVRNG(*CURRENT) JRNCDE((T)) ENTTYP(CD)

USRPRF(*ALL) OUTPUT(*OUTFILE) OUTFILFMT(*TYPE5)

OUTFILE(MYLIBRARY/CDENTRIES2) OUTMBR(*FIRST *REPLACE)

ENTDTALEN(*RCDFMT)

Base PF Field Name Field Description Key Tp Pos Len Dec

CDENTRIES JOENTL Length of entry S 1 5 0

JOSEQN Sequence number A 6 20

JOCODE Journal Code A 26 1

JOENTT Entry Type A 27 2

JOTSTP Timestamp of Entry Z 29 26 0

JOJOB Name of Job A 55 10

JOUSER Name of User A 65 10

JONBR Number of Job S 75 6 0

JOPGM Name of Program A 81 10

JOPGMLIB Program Library A 91 10

JOPGMDEV Program ASP Device A 101 10

JOPGMASP PROGRAM ASP S 111 5 0

JOOBJ Name of Object A 116 10

JOLIB Objects Library A 126 10

JOMBR Name of Member A 136 10

JOCTRR Count or relative record A 146 20

JOFLAG Flag A 166 1

JOCCID Commit cycle identifier A 167 20

JOUSPF User Profile A 187 10

JOSYNM System Name A 197 8

JOJID Journal Identifier A 205 10

JORCST Referential Constraint A 215 1

JOTGR Trigger A 216 1

JOINCDAT Incomplete Data: 1 or 0 A 217 1

JOIGNAPY Ignored by APY/RMVJRNCHG: A 218 1

JOMINESD Minimized ESD: 0, 1, or 2 A 219 1

JOOBJIND OBJECT INDICATOR: 1 or 0 A 220 1

JOSYSSEQ System Sequence A 221 20

JORCV Receiver A 241 10

JORCVLIB Receiver Library A 251 10

JORCVDEV RECEIVER ASP Device A 261 10

JORCVASP RCV ASP S 271 5 0

JOARM Arm Number S 276 5 0

JOTHD Thread Identifier H 281 0

JOTHDX THREAD ID HEX A 289 16

JOADF Address Family A 305 1

JORPORT Remote Port S 306 5 0

JORADR Remote Address A 311 46

JOLUW Logical Unit of Work A 357 39

JOXID Transaction ID A 396 140

JOOBJTYP Object Type A 536 7

JOFILTYP File Type Indicator A 543 1

JOCMTLVL Nested Commit Level A 544 7

JORES Reserved A 551 5

JONVI Null Value Indicators - V V 558 50

JOESD Entry Specific Data - Var V 610 100

Here is shown the standard record layout for the *TYPE5 *OUTFILE format when the DSPJRN command is used and OUTFILE format *TYPE5 is specified with the default value ENTDTALEN(*RCDFMT). When the ENTDTALEN(*RCDFMT) is specified, the resultant Entry Specific Data (JOESD) is truncated to 100 characters, in effect cutting off the CL command midstream as shown below.

Field Name Field Description Field Value

JOESD Entry Specific Data - Var CDSPJRN QSYS *CMD NQSYS/

DSPJRN JRN(QAUDJRN) RCVRNG(*CURRENT

) JRNCDE((T)) ENTTYP(CD) USRPRF

When the ENTDTALEN is specified as *CALC, however, the entire CL command is extracted into the JOESD field, as shown here.

DSPJRN JRN(QAUDJRN) RCVRNG(*CURRENT) JRNCDE((T)) ENTTYP(CD)

USRPRF(*ALL) OUTPUT(*OUTFILE) OUTFILFMT(*TYPE5)

OUTFILE(MYLIBRAR/CDENTRIES2) OUTMBR(*FIRST *REPLACE)

ENTDTALEN(*CALC)

Field Name Field Description Field Value

JOESD Entry Specific Data - Var CDSPJRN QSYS *CMD NQSYS/

DSPJRN JRN(QAUDJRN) RCVRNG(*CURRENT

) JRNCDE((T)) ENTTYP(CD) USRPRF(*AL

L) OUTPUT(*OUTFILE) OUTFILFMT(*TYPE

5) OUTFILE(MYLIBRAR/CDENTRIES2) OUT

MBR(*FIRST *REPLACE) ENTDTALEN(*CAL

C)

Parsing the Journal Entry Specific Data (ESD)

As you can see from the JOESD (Entry Specific Data) field in each of the preceding output file formats, there are actually several pieces of information imbedded in the one JOESD field. When these fields are parsed, what you have is the information shown in here.

Type of entry C

Name of object DSPJRN

Library name QSYS

Object type *CMD

Command run from CL Pgm? N

The CL Command string DSPJRN JRN(QAUDJRN) RCVRNG(*CURRENT

) JRNCDE((T)) ENTTYP(CD) USRPRF(*AL

L) OUTPUT(*OUTFILE) OUTFILFMT(*TYPE

5) OUTFILE(MYLIBRAR/CDENTRIES2) OUT

MBR(*FIRST *REPLACE) ENTDTALEN(*CAL

C)

But the DSPJRN command doesn't naturally parse these fields for you, so your reporting facility must parse this JOESD field for you. That is, unless the *OUTFILE is first created, as we will see in a moment.

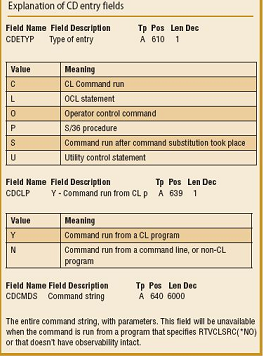

However, the CPYAUDJRNE command does parse the ESD for you. The outfile format used by CPYAUDJRNE CD is shown here, in which you can see that these ESD fields are already parsed for you (at the highlighted area).

Base PF Field Name Field Description Key Tp Pos Len Dec

QAUDITCD CDENTL Length of entry S 1 5 0

CDSEQN Sequence number A 6 20

CDCODE Journal code A 26 1

CDENTT Entry type A 27 2

CDTSTP Timestamp of entry Z 29 26 0

CDJOB Name of job A 55 10

CDUSER Name of user A 65 10

CDNBR Number of job S 75 6 0

CDPGM Name of program A 81 10

CDPGMLIB Program library A 91 10

CDPGMDEV Program ASP device A 101 10

CDPGMASP Program ASP number S 111 5 0

CDRES1 Not used A 116 71

CDUSPF User profile A 187 10

CDSYNM System name A 197 8

CDRES2 Not used A 205 16

CDSYSSEQ System sequence A 221 20

CDRCV Receiver A 241 10

CDRCVLIB Receiver Library A 251 10

CDRCVDEV Receiver ASP device A 261 10

CDRCVASP Receiver ASP number S 271 5 0

CDARM Arm number S 276 5 0

CDTHREAD Thread identifier H 281 0

CDTHRDHX Thread ID hex A 289 16

CDADF Address family A 305 1

CDRPORT Remote port S 306 5 0

CDRADR Remote address A 311 46

CDRESA Not used A 357 249

CDESDL Length of specific data B 606 5 0

CDETYP Type of entry A 610 1

CDONAM Name of object A 611 10

CDOLIB Library name A 621 10

CDOTYP Object type A 631 8

CDCLP Y - Command run from CL p A 639 1

CDCMDS Command string A 640 6000

CDASP ASP name for command libr A 6640 10

CDASPN ASP number for command li A 6650 5

There Is a Better and Far Easier Way!

In analyzing the extraction command CPYAUDJRNE, I was curious about what it was actually doing, so I turned on auditing for my user profile and ran the CPYAUDJRNE command. I then reviewed the output of the CD (Command Execution) journal entries. The output showed the CL commands that the CPYAUDJRNE command was running. The command was creating a duplicate object from the IBM-supplied model outfile for CD entries, and then the CPYAUDJRNE command was actually running the DSPJRN command.

In effect, you can mimic this process to get the best of both commands. When extracting the CD entries, which identify the command execution events, you copy the IBM-supplied model outfile that CPYAUDJRNE uses and then run the DSPJRN command using the *TYPE5 outfile format, but you must specify that the output file will be your copy of the IBM model outfile. Here is an example that you can follow.

1. Create a duplicate of the IBM-supplied model outfile for CD entries:

CRTDUPOBJ OBJ(QASYCDJ5) FROMLIB(QSYS) OBJTYPE(*FILE) TOLIB(MYLIB) NEWOBJ(CD_MODEL)

2. Run the DSPJRN command and specify *TYPE5 and the name of your copy of the IBM model outfile:

DSPJRN JRN(QAUDJRN) RCVRNG(*CURRENT) JRNCDE((T)) ENTTYP(CD) USRPRF(*ALL)

OUTPUT(*OUTFILE) OUTFILFMT(*TYPE5) OUTFILE(MYLIB/CD_MODEL) OUTMBR(*FIRST *REPLACE)

When you're using the IBM-supplied model outfile QASYCDJ5, all the data fields are already parsed for you from the JOESD, so your reporting facility doesn't have to do the parsing work.

About DSPJRN Outfiles and the ESD for CD Entries

CPYAUDJRNE uses the IBM model file QASYxxJ5, where xx is the journal entry type, as in CD. So for CD entries, the model file is QASYCDJ5, for AF entries the model file is QASYAFJ5, and so forth.

Some of the fields in the QASYCDJ5 file that is used to report the CD(Command String) entries require further explanation.

Slice and Dice

Once the data has been extracted to the model outfile for that journal entry type by using the DSPJRN or CPYAUDJRNE command, you can use your favorite query tool to create your custom reports. You can also download the file to your PC and manipulate it in Excel or other PC programs. Slice and dice as needed.

In the next installment of this QAUDJRN forensic analysis series, I examine other auditing configuration and reporting options. In the meantime, begin auditing those activities and events that you will need to report.

About the Author

Dan Riehl is the Editor of the SecureMyi Security Newsletter and a Security Specialist for

Dan Riehl is the Editor of the SecureMyi Security Newsletter and a Security Specialist for

the

IT Security and Compliance Group, LLC.

Dan performs IBM i security assessments and provides security consulting, remediation, forensic evaluations, and other customized security

services for his clients. He also provides training in all aspects of IBM i security and other technical areas through The 400 School, Inc.

Dan Riehl on LinkedIn

|